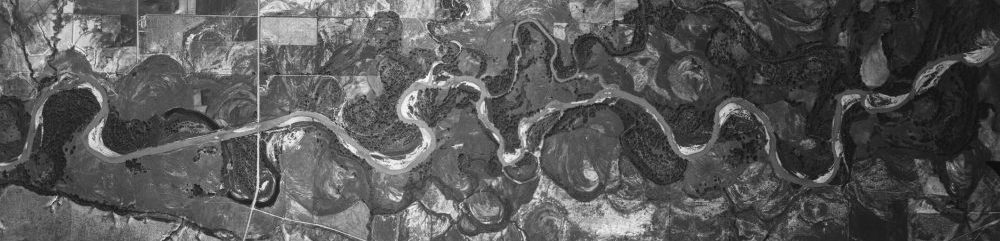

Only a small proportion of the rivers of the contiguous United States remain in a fully functional, natural state: about 2% of the total length of US rivers remain unaffected by dams, for example. People indirectly alter rivers by changing the characteristics of the land surface that supplies water, sediment, solutes, and organic matter to the rivers. We change vegetation communities through timber harvest, grazing, crops, and urbanization and we alter topography by building roads and cities. People also directly alter river corridors. We drain floodplains to use the land for agriculture or cities. We build artificial levees to keep water within channels and off floodplains and we build dams and divert flow from the river corridor. We straighten and deepen channels and then artificially stabilize the streambanks to keep the channel from eroding. We introduce non-native woody species that change the configuration and stability of the channel and floodplain, or aquatic species that alter the food web within the channel. We remove large wood capable of forming logjams and beavers capable of building dams, and these removals simplify and homogenize the river corridor.

The list of ways in which humans alter river ecosystems is very long and the list of rivers in the US affected by these alterations is even longer. Why does this matter? The net effect of human alterations is to simplify and homogenize river corridors. We simplify the physical configuration of the river corridor and we simplify the fluxes of water and sediment into and down the river corridor. These simplifications reduce the physical and ecological integrity of the river. Ecosystem services provided by the river decline or, sometimes, disappear.

Because of the longitudinal connectivity within river networks, changes affecting the smallest headwater streams can also have substantial cumulative effects downstream in much larger rivers. The Gulf of Mexico receives massive amounts of nitrates from the Mississippi River, for example, because each of the many smaller rivers within the Mississippi River drainage network contributes its share of excess nitrate.

Overall, human alterations to river ecosystems can be summarized in the following broad categories: