Rivers as ecosystems

A river is more than simply a channel that conveys water downstream. A river is an ecosystem that supports a wide array of living organisms and provides numerous ecosystem services. The river ecosystem relies on the interconnectedness of the basic physical components of a river – the channel, the adjacent floodplains that are periodically inundated by water from the channel, and the underlying hyporheic zone in which water repeatedly moves between the channel and the subsurface. Water, solutes, sediment, and organic matter move downstream with time, but these movements have a three-dimensional character that reflects exchanges between the channel, floodplain, and hyporheic zone. This three-dimensional connectivity is important to maintaining the river ecosystem, as is the longitudinal connectivity at the scale of an entire river network. Connectivity within a river corridor and a river network means that changes in the headwaters of a network can affect the mainstem river, as when dams on smaller rivers limit upstream migration of fish or excess nitrates coming into headwaters overwhelm the ability of the mainstem river to biologically process these nutrients.

A river ecosystem is inherently dynamic. Each year’s snowmelt or wet-season rainfall increases flow in the channel and inundates the floodplain. Heavy rainfall creates a flood that moves sediment within the channel and floodplain, changing the shape of the river. A wildfire removes the vegetation covering hillslopes surrounding the river and large fluxes of water and sediment change the river’s shape. Sometimes these extreme events create lasting change in the river corridor; sometimes the changes are transient. Every change that occurs can kill some organisms and destroy habitat yet change also creates new habitat and opportunities for other organisms. Plants and animals living within and along rivers have adapted to this changeable environment and commonly rely on the regular seasonal fluctuations and less predictable episodic disturbances to maintain habitat and food supplies.

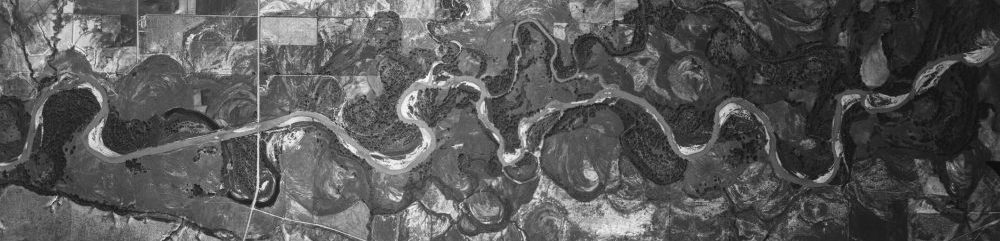

A river ecosystem is also spatially heterogeneous. Follow a natural river downstream. Pools will alternate with riffles or rapids; steep, narrower segments of the valley in which only a slender floodplain borders the channel will alternate with gentle, wider segments in which the channel may branch across a wide floodplain into secondary channels that rejoin downstream. This spatial heterogeneity equates to diverse habitat that can support a greater variety of organisms and different life stages of a particular organism – shallow, warm water habitat for young fish and spawning gravels for the breeding adults, or newly deposited bars on which seedlings can germinate and stable bank habitat for mature trees.

Moving downstream from the smallest headwater streams, which are more likely to be ephemeral and flow only after rainfall or snowmelt, the mainstem channel typically grows progressively larger. The mainstem may remain ephemeral in deserts, but in wetter climates the river is likely to be perennial and contain at least some flowing water throughout the year.

A fully functional natural river can respond to regular, seasonal fluctuations in water and sediment inputs and to episodic extreme events. If flow in the channel increases, the extra flow energy creates erosion of the channel bed and banks or the water moves out of the channel to inundate the floodplain. If more sediment enters the river corridor, bars form in the channel or sediment deposition raises the level of the floodplain. A river that is able to adjust to changing inputs exhibits physical integrity and this helps to support ecological integrity, which is the degree to which a diverse community of native organisms is maintained.

A functional natural river also provides ecosystem services that people value, including flood control when flood waters spread across the floodplain and move downstream more slowly; clean water when microbial communities living in floodplain soils help to remove excess nitrate from river water; fisheries when diverse and abundant habitat support abundant fish populations; recreation from fishing to paddling and bird-watching to bicycling; and carbon sequestration when wet floodplain soils accumulate organic matter and develop high concentrations of organic carbon.

Follow the links below to see how humans have altered river ecosystems across the US and why there are reasons to hope that such alterations are not irreversible death sentences, but challenges that can be overcome.

Human alterations of river ecosystems